For Lakeview Middle School Assistant Principal, Ed Román, equity always begins with the needs of the child in front of him.

“We have an ESOL student who came into the country last year, and was placed in the 4th grade,” he shares. “But physiologically, we found out he was 13 years old! He speaks Chuj, the Guatemalan dialect, and some Spanish. What is the most appropriate educational program for this child? Is there a significant learning disability? You want to do what’s right for the child, but it’s hard to do because these children need such customized supports.”

His goal as a public school administrator is to untangle the services, policies, and poverty surrounding young learners, realigning the social determinants of learning so that they work for students, instead of against them.

“I have to make sure that the school is ready to teach, and the child is ready to learn,” he explains. “That doesn’t work out so well if the child is hungry… Anything that keeps the child from being the best learner is an equity concern.”

His concern for children striving to learn despite life struggles is a personal one. The hard work and potholes of Ed’s immigrant experience are an intimate reminder of the odds he overcame to achieve a career in educational leadership that has been running strong for 26 years.

Ed was born in Chile, which, in the 1970s was not a place of opportunity for entrepreneurs. Ed’s father journeyed and worked for years seeking a country where he would be free to run his own business to support his family. Finally, when he was 10, the family left post-revolutionary Chile to reunite in Connecticut. Working in the blue collar labor of his father’s roofing business and service industry jobs of his teens lit “a burning desire to be a professional,” as he puts it.

The most important equity issue in education for Ed is fueled by personal experience: “to ensure that high school students have the support…to find an academic program that makes sense for them for their transition out of high school.” Like many working class students, he started college, dropped out, and re-enrolled—always working a job alongside his classes. He admits that his grades weren’t the best, but he chose education because he could see his future self in the role of the teachers who pushed him to succeed. He wanted to give that support to other students in tough situations. “I knew I had a good story.”

“I believed in public education, and I believed that I could give back,” he recalls.

This conviction would lead him to some of his most impactful work with immigrant youth.

Ed has been recruited for and excelled in the types of teaching situations that many trained educators avoid. Often it is a large scale issue or programmatic need that warrants his placement. “I’ve been asked to get things started or turn things around. I go with an assignment in mind,” he explains.

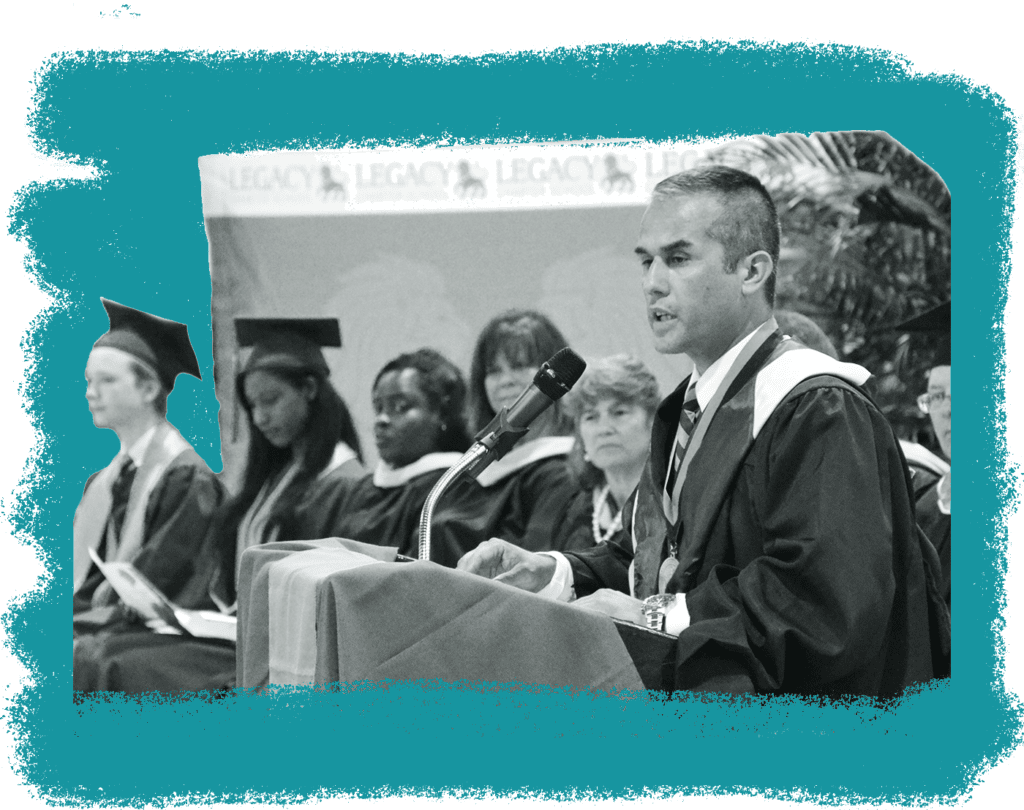

He began by teaching social studies in inner-city New Haven, and then inner-city Jacksonville, while earning his M.A. in Educational Leadership. Once in Greenville, he began connecting deeply with the Hispanic community as the principal of Legacy Early College. In reaching out to find resources for families, he met Adela Mendoza and Hispanic Alliance. They joined forces, forging a successful relationship between Hispanic Alliance and Legacy. The school hosted financial classes for Hispanic families, and the very first information sessions and workshops on then-new DACA status, the first time undocumented immigrant youth had any hope of higher education.

Despite vocal opposition from state legislators, Ed continued to champion education for undocumented students. DACA opened a world of educational possibilities, and he stood up for that hope by supporting the planning and implementation of the Student DREAMers Alliance (SDA)*, the Hispanic Alliance’s answer to the subsequent SC legislation that forced DACA recipients to pay out-of-state tuition. He volunteered with Hispanic Alliance Lunch and Learns and College Fairs, helping students with few options chart every possible avenue to success.

“For poor kids education doesn’t make sense,” he explains, “There are no adults saying ‘Go to college so you can have a job like me.’ Inner city kids don’t have that. Poor kids don’t have that, immigrant kids don’t have that. I made sure that kids understood the value of their education and that there is a pathway for them.”

Ed now chairs the Education Community Team for Hispanic Alliance, and does so during a year when the COVID-19 pandemic has widened the existing gap for students without resources at home. “Is the internet running well? Is there space for them to learn? Is it free of disruptions? Many times that’s not the case,” he states. It was Ed’s persistent warnings that brought home the incredible risk to students with Spanish-speaking families as they transitioned into eLearning with no preparation. He speaks with candor about the grittier lived experiences of his students, without objectifying them. Currently, he points to young teens who became pregnant since March, and older teens who never returned to school in August – demonstrating the high price of minimal contact education for at-risk students. “The stakes are high,” he insists. “Each day is critical.”

For the last 10 years, Hispanic Alliance has stood for equity within a particularly hostile social and legislative environment. That’s why Ed is the perfect collaborator—he is drawn to the challenge and committed to the most disenfranchised. This year has ripped gaping holes in the fabric of public education, and Hispanic students are falling through unseen. Neither the force that is Assistant Principal Román, nor Hispanic Alliance can protect equity alone. We hope his story inspires you to join us in Standing For Equity!